Blog

The tuck box

Back in the mid-1990s, I started to work on a memoir/cookbook about growing up in Jamaica where I spent the first 16 years of my life. I managed to write about 90 pages, or 26,951 words. I even sent it to a book agent, who told me that it was not the type of book she represented, but encouraged me to shop it around. I think she was being kind. I never did finish it.

Out of curiosity, I went back to read it and found lots of interesting stories sprinkled throughout. One of them was titled No Soul Food Here about some of my experiences in a Catholic boarding school. Not among my fondest memories, but it sure gave me lots to write about!

This story brought back memories of the boarders’ survival kit: the tuck box. At the beginning of each term, we would pack up a box of snacks and goodies to help us through the first few weeks of notoriously unpalatable boarding school food. It’s sort of like the care packages people send to family members deployed overseas. Or in my case, the boxes of snacks I send to the grandkids. It may be a throwback to my tuck box days, as lord knows, those kids don’t lack for snacks!

I like sending unusual stuff that they can’t easily get in Oregon. Like fried pigs ears, Chinese pretzels made right here in Kaneohe, bamboo charcoal peanuts, kiawe barbecue taro chips, Paniolo beef jerky, local made arare and chocolate chip cookies, along with various kinds of arare, and some fun stickers. I’m about to send a box off this week.

In the meantime, here’s a slightly edited excerpt from my abandoned book, Caribbean Stir-Fry: Chinese Roots, Jamaican Flavors. The language is a bit florid and overwrought, but hey, don’t judge. I wrote it more than 20 years ago!

No Soul Food Here

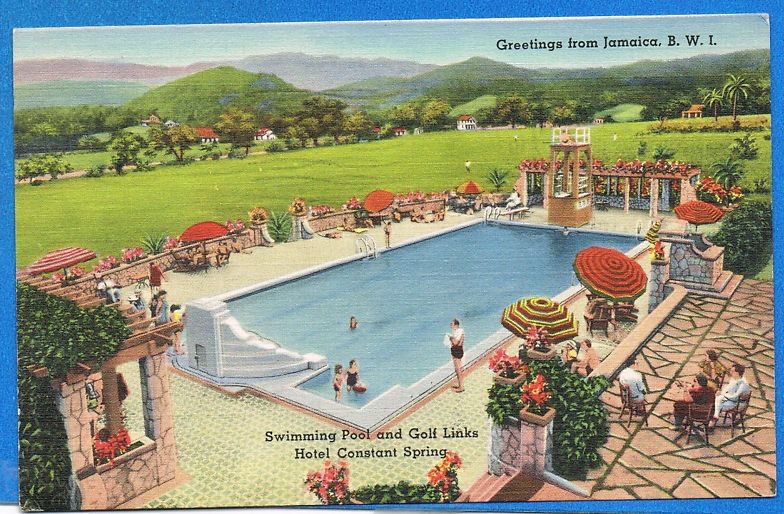

Boarding schools are not known for their cuisine. Immaculate Conception High School in Constant Spring, Kingston, Jamaica was no exception. It was particularly pathetic when seen in the context of the school’s architectural grandeur. There is a certain irony in the location of this strict Catholic girls school that was run like a boot camp by an order of Franciscan nuns from upstate New York. Controls may have loosened up over the decades, but in my day during the 1950s, its brand of regimentation and discipline was meted out lavishly. It contrasted crazily with the elegant pink four-story Spanish-style arcaded former hotel where celebrities cavorted.

Our school was formerly the Constant Spring Hotel, a swank resort for the rich and famous. In my overheated pubescent imagination, I fantasized torrid assignations between handsome men like swashbuckling Errol Flynn and Tyrone Power and glittering, glamorous femme fatales like Rita Hayworth and Hedy Lamar — all of whom I watched raptly on the movie screen. Most of you reading this may need to Google them.

My own Catholic guilt at conjuring up such scandalously titillating scenes fueled by Hollywood gave me ample grist for the weekly confessional mill, ambiguously offered up as "impure thoughts." It made sense, then, that such a hotel would fall on hard times and into the hands of the guardians of morality and our collective chastity (sometimes a losing battle, as we'd suspect when a classmate left our ranks suddenly, without explanation).

The spacious campus boasted a huge swimming pool fed by a three-tiered fountain topped by a swan, a carefully manicured formal sunken garden, and generous grounds for leisurely strolls, though none of these were enjoyed often by its inmates.

Most of the dormitory rooms, formerly guest rooms, opened onto balconies, some with views of the green hills beyond and the lush golf course that embraced two sides of our campus. While several boarders shared a room, we had the unusual luxury of our own bathroom with a deep tub and lots of hot water. Never mind that we were never in the room long enough to enjoy the amenities — just enough to get a good night's sleep or for the obligatory rest hours on Saturdays and Sundays, all conducted in grand silences.

Silence was a great weapon at ICHS. When our natural youthful exuberance exceeded the bounds of nunnish tolerance, a bell would inevitably ring followed by the command for quiet. Meals were eaten mostly in silence, because we were incapable of learning the genteel art of light, ladylike conversation. We would frequently be cut off in mid-sentence by a sister who would sit at one end of the refectory, reading her prayers. (I think she was mostly bored.) We also sat for hours in study hall, both in the afternoon and evening, mute and bored. We became masters at surreptitious note-passing. Even our recreation periods would be cut short if voices became too boisterous, laughter too raucous, and the long playing records of ardently romantic Latin American music we loved was too heated.

It was never enough that silence was imposed. It had to be monitored. I can remember after lights out, the dormitory room door being flung open, the overhead light blazing in the guilty darkness, as Sister “D”, the headmistress and head storm trooper thundered out her displeasure at the whispering she had detected on her stealthy check of the corridors. She was a master of the prowl. The wooden beads of her rosary never ever gave her away.

But I was talking about convent cuisine. A contradiction in terms, if ever there was one. The long-gone executive chef of the Constant Spring Hotel would have winced and thrown up his haute cuisine hands in despair at what issued from his stainless steel kitchen. I can't remember being served Jamaican or any other identifiable ethnic foods. Simply nondescript, boring institutional food.

My memory fails me — probably finding it incredulous that such bland fare could dare to be served in a land of such wildly articulate cuisine. There were the unappetizing mounds of plain pureed pumpkin, its virginal state untouched by cinnamon or nutmeg or even butter, and a runny, pale yellow mess masquerading as scrambled egg. I suspect it was reconstituted from a powdered form.

Then there was the infamous "SOS", the mystery meat drowned in a white sauce and poured over timid white toast. The only other institution we knew of that served this dish was the U.S. Army.

One of the most unpopular desserts was tapioca pudding. My niece, Christine, who went to Immaculate after I had left, remembers the servers clearing the tables of full dessert dishes, which they would pile one of top of the other, and the tapioca would flow out like a waterfall over the sides making a gluey mess.

What made boarding school food tolerable, though, was the tuck box. At the beginning of term, many of us brought our personal supply of non-perishable goodies that was stored in the refectory. For the first week or so, recess-time was a feast of saltine crackers, saloon pilots, Vienna sausages, sardines, bully beef (the Jamaican term for canned corned beef), Pickapeppa sauce and condensed milk (to pour on the saloon pilots), tins of Ovaltine and Milo drink mixes, Horlick's malted milk balls, plus an assortment of Black Magic, Kit Kat and Cadbury's chocolates, and Peak Freans cookies. If I was lucky, and our cook, Vyra was feeling generous, a homemade butter cake in a tightly covered tin would find its way into a corner of my tuck box. Too soon, my provisions would be depleted, and it was time to line up under the tree at recess time, waiting my turn to buy treats at the snack table. I’m not sure how I would have survived boarding school otherwise.

SOS *

This is not the ICHS version of SOS, but it gives you the idea.

1 lb. ground beef or 1 can corned beef

1/2 small onion minced

2 cloves of garlic minced

1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon thyme

2 tablespoons flour

2 1/2 cups milk

Salt and pepper

Dash of tabasco

Dash of Worcestershire sauce

Brown ground beef or corned beef. Add onion and garlic and cook for two to three minutes. Add flour and mix in well. Stir in milk and remaining ingredients, and cook until thickened. Serve over toast.

- http://www.cooksinfo.com/shit-on-a-shingle: Shit on a Shingle (SOS) is an (unofficial) US military food term. It generally implies some kind of meat in a sauce, served over toast (the toast being the "shingle"), often served as a breakfast dish.

The passage of time

should heal the tortured palate.

It’s still all too fresh.